Earth Structure: A virtual journey to the center of Earth

Listen to this reading

Did you know that although earthquakes can be very destructive, they provide a wealth of information about Earth's interior? Miners, geologists, and others have always wondered what lies below the surface of Earth, but heat and pressure make it impossible to explore deep into its interior. However, seismic waves produced by earthquakes reveal the structure and composition of our planet.

The deepest places on Earth are in South Africa, where mining companies have excavated 3.5 km into Earth to extract gold. No one has seen deeper into Earth than the South African miners because the heat and pressure felt at these depths prevents humans from going much deeper. Yet Earth's radius is 6,370 km – how do we begin to know what is below the thin skin of the Earth when we cannot see it?

Evidence about Earth's interior

Isaac Newton was one of the first scientists to theorize about the structure of Earth. Based on his studies of the force of gravity, Newton calculated the average density of Earth and found it to be more than twice the density of the rocks near the surface. From these results, Newton realized that the interior of Earth had to be much denser than the surface rocks. His findings excluded the possibility of a cavernous, fiery underworld inhabited by the dead, but still left many questions unanswered. Where does the denser material begin? How does the composition differ from surface rocks?

Volcanic vents like Shiprock occasionally bring up pieces of Earth from as deep as 150 km, but these rocks are rare, and we have little hope of taking Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth. Instead, much of our knowledge about the internal structure of the Earth comes from remote observations – specifically, from observations of earthquakes.

Earthquakes can be extremely destructive for humans, but they provide a wealth of information about Earth's interior. This is because every earthquake sends out an array of seismic waves in all directions, similar to the way that throwing a stone into a pond sends out waves through the water. Observing the behavior of these seismic waves as they travel through the Earth gives us insight into the materials the waves move through.

Comprehension Checkpoint

Seismic waves

An earthquake occurs when rocks in a fault zone suddenly slip past each other, releasing stress that has built up over time. The slippage releases seismic energy, which is dissipated through two kinds of waves, P-waves and S-waves. The distinction between these two waves is easy to picture with a stretched-out Slinky®. If you push on one end, a compression wave passes through the Slinky® parallel to its length (see P-waves video). If instead you move one end up and down rapidly, a "ripple" wave moves through the Slinky® (see S-waves video). The compression waves are P-waves, and the ripple waves are S-waves.

Both kinds of waves can reflect off of boundaries between different materials: They can also refract, or bend, when they cross a boundary into a different material. But the two types of waves behave differently depending on the composition of the material they are passing through. One of the biggest differences is that S-waves cannot travel through liquids whereas P-waves can. We feel the arrival of the P- and S-waves at a given location as a ground-shaking earthquake.

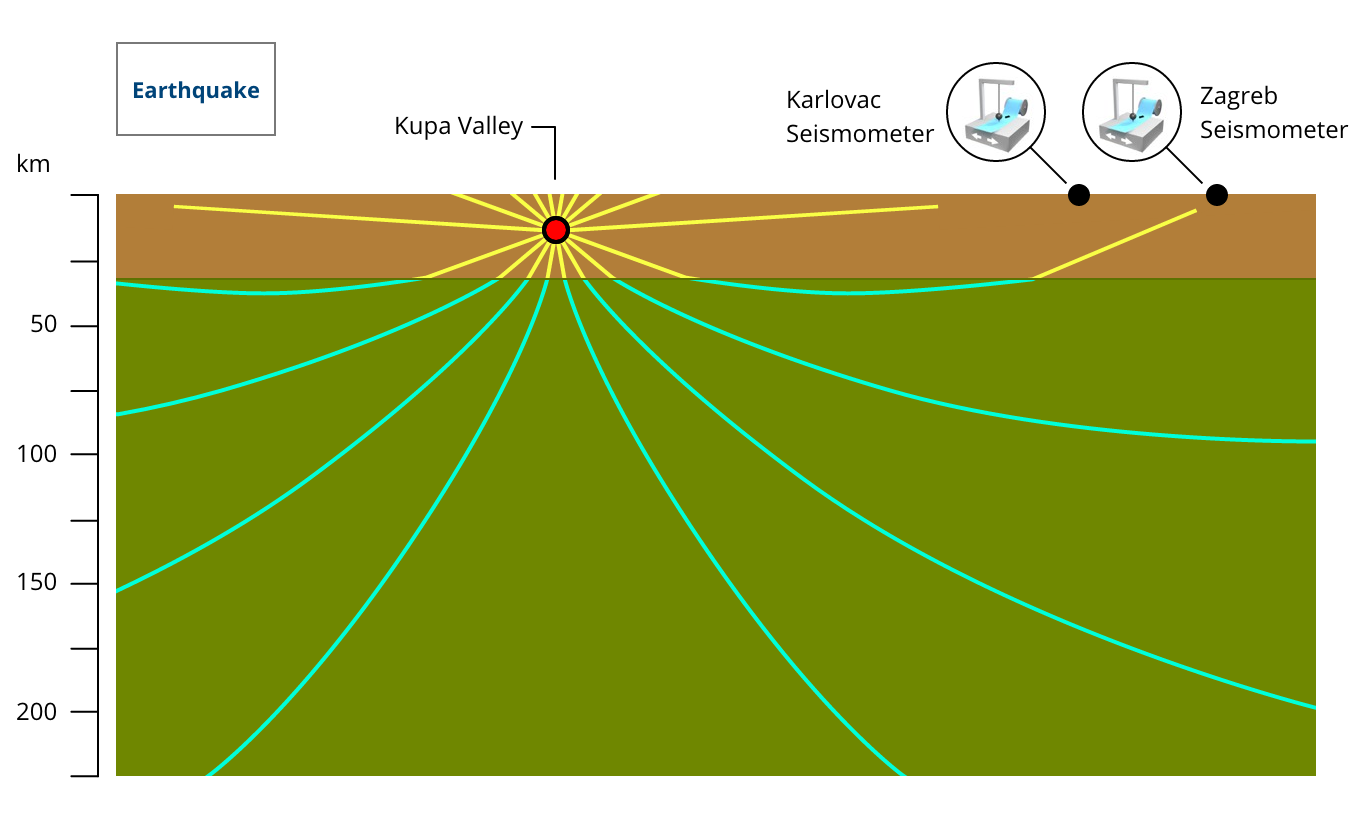

If Earth were the same composition all the way through its interior, seismic waves would radiate outward from their source (an earthquake) and behave exactly as other waves behave – taking longer to travel further and dying out in velocity and strength with distance, a process called attenuation. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Seismic waves in an Earth of the same composition.

Given Newton's observations, if we assume Earth's density increases evenly with depth because of the overlying pressure, wave velocity will also increase with depth and the waves will continuously refract, traveling along curved paths back towards the surface. Figure 1 shows the kind of pattern we would expect to see in this case. By the early 1900s, when seismographs were installed worldwide, it quickly became clear that Earth could not possibly be so simple.

The Moho

Andrija Mohorovičić was a Croatian scientist who recognized the importance of establishing a network of seismometers. Though his scientific career had begun in meteorology, he shifted his research pursuits to seismology around 1900, and installed several of the most advanced seismometers around central Europe in 1908. His timing was fortuitous, as a large earthquake occurred in the Kupa Valley in October 1909, which Mohorovičić felt at his home in Zagreb, Croatia. He made careful observations of the arrivals of P- and S-waves at his newly-installed stations, and noticed that the P-waves that measured more than 200 km away from an earthquake's epicenter arrived with higher velocities than those within a 200 km radius. Although these results ran counter to the concept of attenuation, they could be explained if the waves that arrived with faster velocities traveled through a medium that allowed them to speed up, having encountered a structural boundary at a greater depth.

This recognition allowed Mohorovičić to define the first major boundary within Earth’s interior – the boundary between the crust, which forms the surface of Earth, and a denser layer below, called the mantle (Mohorovičić, 1910). Seismic waves travel faster in the mantle than they do in the crust because it is composed of denser material. Thus, stations further away from the source of an earthquake received waves that had made part of their journey through the denser rocks of the mantle. The waves that reached the closer stations stayed within the crust the entire time. Although the official name of the crust-mantle boundary is the Mohorovičić discontinuity, in honor of its discoverer, it is usually called the Moho (see the interactive animation below).

Interactive Animation: Moho

Shadow zones

Another observation made by seismologists was the fact that P-waves die out about 105 degrees away from an earthquake, and then reappear about 140 degrees away, arriving much later than expected. This region that lacks P-waves is called the P-wave shadow zone (Figure 2). S-waves, on the other hand, die out completely around 105 degrees from the earthquake (Figure 2). Remember that S-waves are unable to travel through liquid. The S-wave shadow zone indicates that there is a liquid layer deep within Earth that stops all S-waves but not the P-waves.

Figure 2:The P-wave and S-wave shadow zones.

In 1914, Beno Gutenberg, a German seismologist, used these shadow zones to calculate the size of another layer inside of the Earth, called its core. He defined a sharp core-mantle boundary at a depth of 2,900 km, where P-waves were refracted and slowed and S-waves were stopped.

Comprehension Checkpoint

The layers of Earth

On the basis of these and other observations, geophysicists have created a cross-section of Earth (Figure 3). The early seismological studies previously discussed led to definitions of compositional boundaries; for example, imagine oil floating on top of water – they are two different materials, so there is a compositional boundary between them.

Later studies highlighted mechanical boundaries, which are defined on the basis of how materials act, not on their composition. Water and oil have the same mechanical properties – they are both liquids. On the other hand, water and ice have the same composition, but water is a fluid with far different mechanical properties than solid ice.

Figure 3: Compositional and mechanical layers of Earth's structure.

image ©Dr. Anne E. Egger CC BY-NC-SA 4.0Compositional layers

There are two major types of crust: crust that makes up the ocean floors and crust that makes up the continents. Oceanic crust is composed entirely of basalt extruded at mid-ocean ridges, resulting in a thin (~ 5 km), relatively dense (~3.0 g/cm3) crust. Continental crust, on the other hand, is made primarily of less dense rock such as granite (~2.7 g/cm3). It is much thicker than oceanic crust, ranging from 15 to 70 km. At the base of the crust is the Moho, below which is the mantle, which contains rocks made of a denser material called peridotite (~3.4 g/cm3). This compositional change is predicted by the behavior of seismic waves and it is confirmed in the few samples of rocks from the mantle that we do have.

At the core-mantle boundary, composition changes again. Seismic waves suggest this material is of a very high density (10-13 g/cm3), which can only correspond to a composition of metals rather than rock. The presence of a magnetic field around Earth also indicates a molten metallic core. Unlike the crust and the mantle, we don't have any samples of the core to look at, and thus there is some controversy about its exact composition. Most scientists, however, believe that iron is the main constituent.

These compositional layers are shown in Figure 3.

Comprehension Checkpoint

Mechanical layers

The compositional divisions of Earth were understood decades before the development of the theory of plate tectonics – the idea that Earth's surface consists of large plates that move (see our Plate Tectonics I module). By the 1970s, however, geologists began to realize that the plates had to be thicker than just the crust, or they would break apart as they moved. In fact, plates consist of the crust acting together with the uppermost part of the mantle; this rigid layer is called the lithosphere and it ranges in thickness from about 10 to 200 km. Rigid lithospheric plates "float" on a layer called the asthenosphere that flows like a very viscous fluid, like Silly Putty®. It is important to note that although the asthenosphere can flow, it is not a liquid, and thus both S- and P-waves can travel through it. At a depth of around 660 km, the pressure becomes so great that the mantle can no longer flow, and this solid part of the mantle is called the mesosphere. The lithospheric mantle, asthenosphere, and mesosphere all share the same composition (that of peridotite), but their mechanical properties are significantly different. Geologists often refer to the asthenosphere as the jelly in between two pieces of bread: the lithosphere and mesosphere.

The core is also subdivided into an inner and outer core. The outer core is liquid molten metal (and able to stop S-waves), while the inner core is solid. (Because the composition of the core is different than that of the mantle, it is possible for the core to remain a liquid at much higher pressures than peridotite.) The distinction between the inner and outer core was made in 1936 by Inge Lehmann, a Danish seismologist, after improvements in seismographs in the 1920s made it possible to "see" previously undetectable seismic waves within the P-wave shadow zone. These faint waves indicated that they had been refracted again within the core when they hit the boundary between the inner and outer core.

The mechanical layers of Earth are also shown in Figure 3, in comparison to the compositional layers.

Our picture of the interior of Earth becomes clearer as imaging techniques improve. Seismic tomography is a relatively new technique that uses seismic waves to measure very slight temperature variations throughout the mantle. Because waves move faster through cold material and slower through hot material, the images they receive help scientists "see" the process of convection in the mantle (see our Plates, Plate Boundaries, and Driving Forces module). These and other images offer a virtual journey into the center of Earth.